©2021 Reporters Post24. All Rights Reserved.

“Return them to their home countries!” flashed my iPhone home screen, accompanied by a red, scowling, furious emoji.

The notification bubble came in reference to a 60-second TikTok video in which I had leaked word that my employer, Stanford University, had just acquired the single largest historical collection of modern Chinese information technology – largest not just in the United States, but the world.

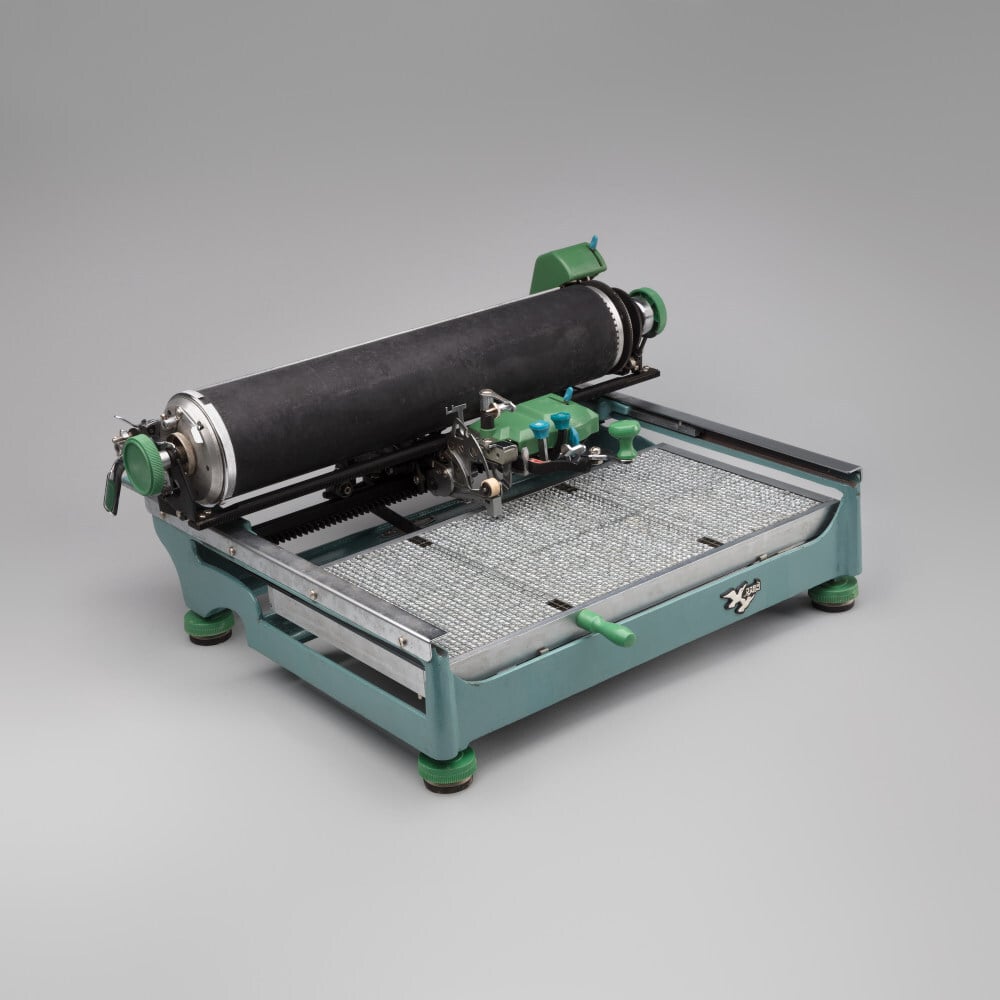

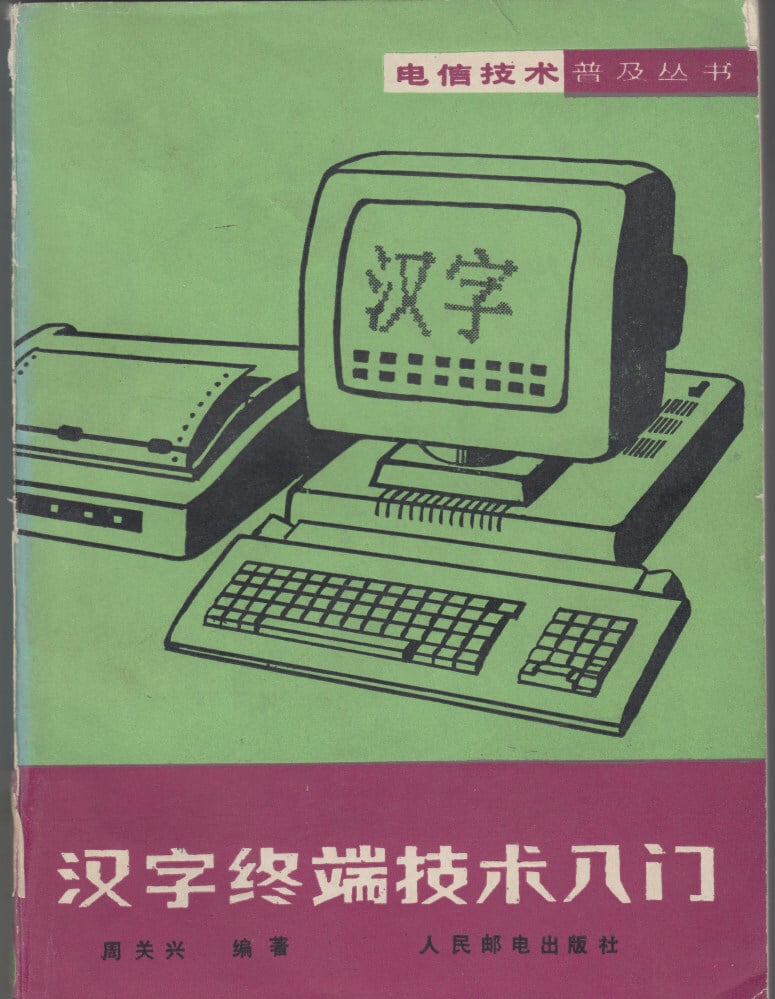

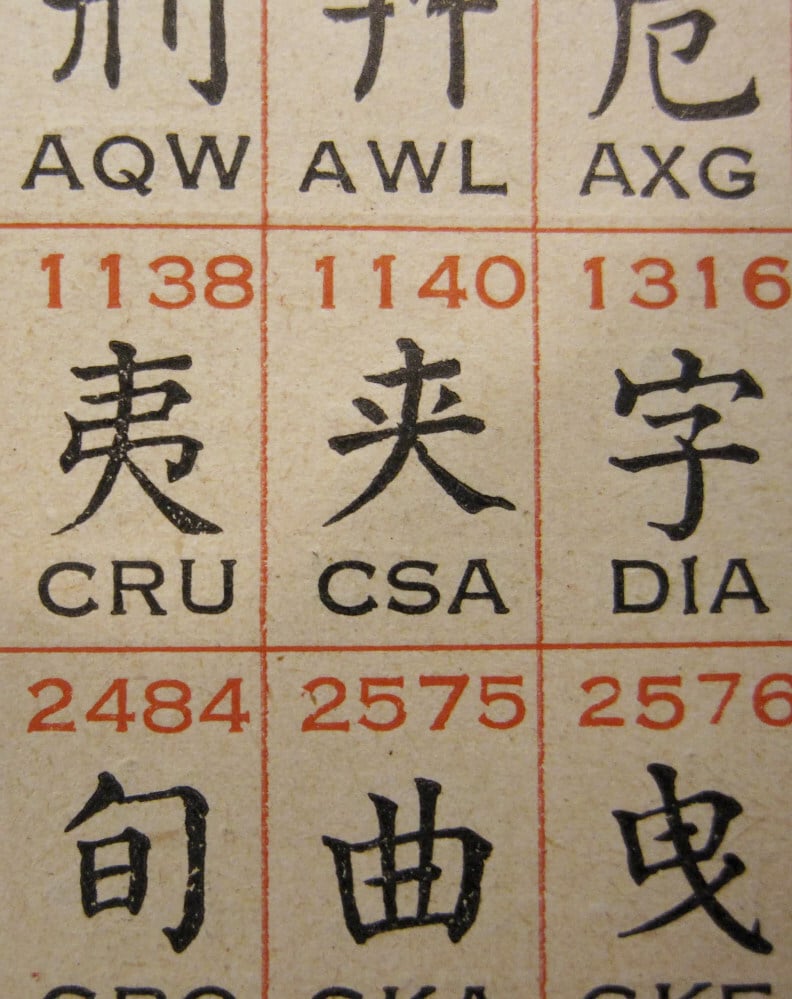

Containing more than 2,500 archival items – including dozens of rare Chinese typewriters, word processors and computers – it covers Chinese-language telegraphy, typewriting, mimeography, bookmaking, mainframe computers, encoding systems, software, operating systems, printers, monitors, fonts, phototypesetting, input systems, word processors, personal computers and more.

It even covers relatively obscure aspects of modern Chinese IT, from the largest collection in the world of Samizdat-style self-published Chinese “zines” to China’s decision in the 1910s to import Western-style punctuation marks, and to the country’s overhaul of government stationery and other kinds of bureaucratic paperwork.

Clearly, the irate commentator believed such artefacts belonged in China, not California. A fair point. And why was this commenter targeting me? Because I am the one who gave Stanford the collection.

There is no shortage of angry commenters on TikTok, of course, particularly when it comes to China-related videos where trolls align fairly neatly into diametrically opposed camps: rabid (often racist) anti-Chinese on the one hand, hyper Sino-nationalists on the other, for whom devotion to country is matched only by staggering fragility to any criticism of it.

Typically, I ignore both camps, but this comment stuck with me. It raised an obvious question: why is the largest collection of modern Chinese IT not housed in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore or elsewhere in the Sinophone world?

Why is this collection called the “Thomas S. Mullaney East Asian Information Technology History Collection”? Also, why was I the one to do this, rather than, say, Tsinghua University, or the Chinese Academy of Sciences? Come to think of it, considering the puissance of China’s current tech industry, why is there not already a museum in China dedicated to the country’s modern IT history?

To begin, we need to take a giant step back, to ask questions about the archives of IT history more broadly. When we do so, we find these archives are profoundly unequal. When it comes to computing history in the US and Europe, scholars enjoy an embarrassment of riches. In California, the Computer History Museum alone is enough to sustain a scholar for their entire career, as are the world-class archival collections held at the Charles Babbage Institute, at the University of Minnesota, to name just two of dozens in the US alone.

And if historians tire of such museums and archives, vast networks of gem-fostering enthusiasts, private collectors and aficionados await.

Historians of modern Chinese IT history face an altogether different challenge, one that I know well, having spent the better part of 15 years writing two books on the subject. Simply put, there is no Chinese equivalent of the Computer History Museum; nothing remotely comparable to the Charles Babbage Institute. Instead, materials are scattered all around the world, in tiny pockets.

In the research for my two-volume history of modern Chinese IT – The Chinese Typewriter: A History (2017) and the forthcoming The Chinese Computer: A History – I worked through more than 50 collections, big and small, located in mainland China, Taiwan, Japan, the US, Italy, Germany, France, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland and Britain.

The transnationalism of these sources is the first step in answering the angry TikToker: modern Chinese information infrastructure has been built not only by engineers working in China and self-identifying as Chinese, but by a vast, diverse, global, and all-but-overlooked cast of characters.

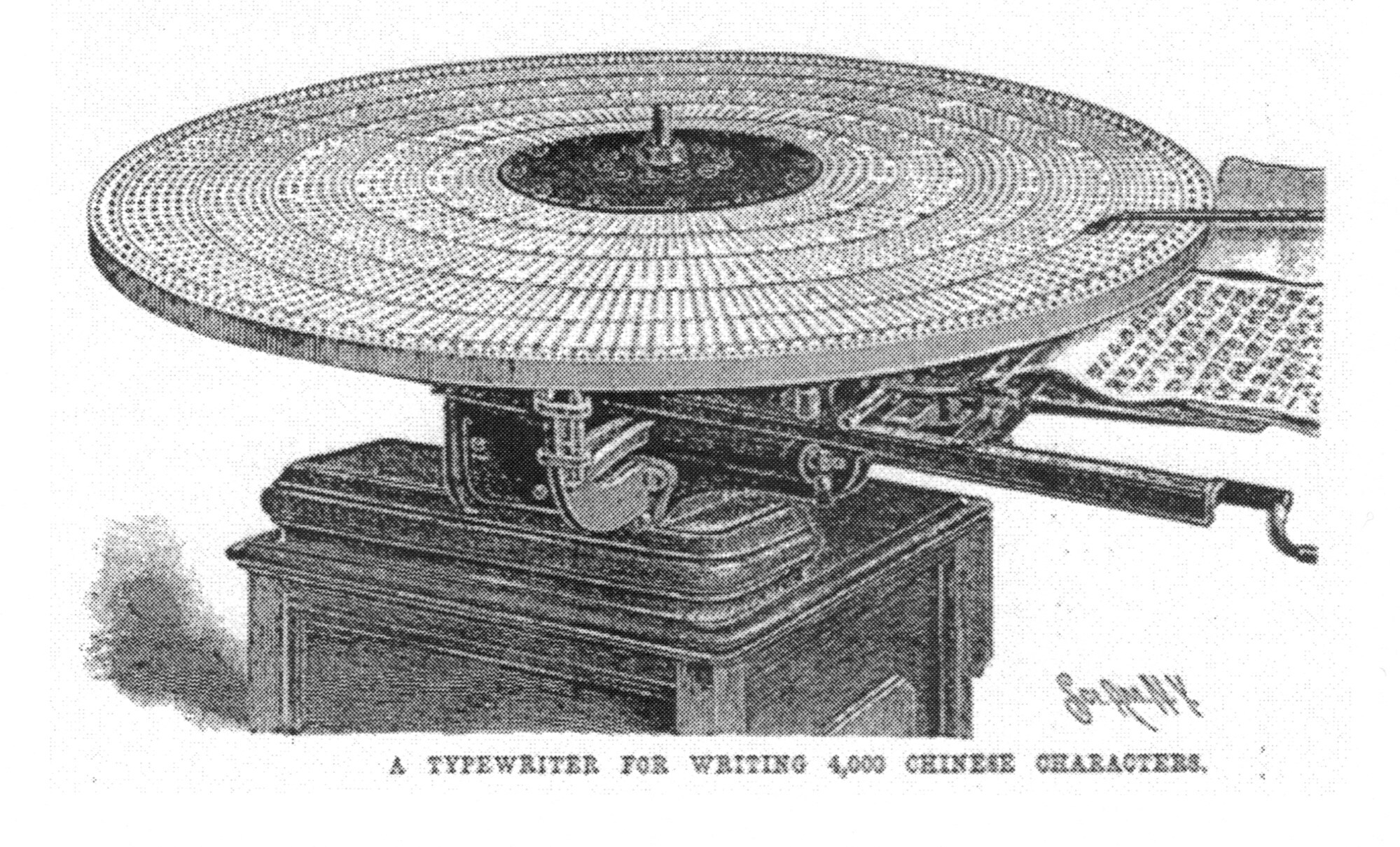

Even when we limit ourselves to just one kind of IT –

– the inventors of these machines include a dizzying array of characters: overseas Chinese students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and New York University at the turn of the 20th century; an American professor of Greek philosophy who spoke not a single word of Chinese; engineers at IBM, Mergenthaler Linotype and the RAND Corporation; linguists at Cambridge University; a former wing commander in Britain’s Royal Air Force; an Australian nuclear physicist turned Chinese typewriter enthusiast; even US government agents in the Office of Strategic Services, later renamed the Central Intelligence Agency (apologies to angry TikTok troll accounts being created at this moment).

Even these were not enough to tell the full story. There were still massive gaps in the history that could not be closed using the collections already out there. So without really meaning to, I started to build my own.

For the first eight years or so, I rummaged through hundreds of second-hand bookshops, junk stores, eBay listings (and their Chinese equivalents), scouring for materials related to Chinese telegraphy, typewriting, printing, word processing, computing and more.

Every time I found something new, I would do what historians are trained to do: read it closely, think about what other sources might be needed to triangulate, make hi-res scans of any graphics I may need to reproduce, cite it in my footnotes, and return it to the shelf.

But then the shelves at home began to fill, then all the other horizontal surfaces, including the floor. Even my garage. I became something of a running joke in my department, as colleagues watched me with my big blue cart, hauling things from my car to my office. One asked if I had started a moving company on the side.

Rather than seeing Chinese telegraphy, typewriting and computing for what they really were … all the Western world could see was a joke

Blogging about my research only made things worse. People began to find me online and offer to give me more stuff. First, a Chinese Christian church in San Francisco gave me its old Chinese typewriter. Then a Japanese church gave me an old kanji typewriter. Soon, I was even receiving offers from people in Britain and librarians working at major American universities. None of these individuals could find a home for their Chinese machines, and I was their last resort. It was either me or the local dump.

It was only in about year 10 that it hit me: I had inadvertently amassed the world’s largest unified collection on the modern history of Chinese and East Asian information technology.

Yes, my angry TikToker, my first instinct was, in fact, to “repatriate”. Reaching out to scholars and colleagues, I searched high and low for something like the Chinese counterpart of the Computer History Museum, a place that perhaps already housed and protected the archives and artefacts of modern Chinese IT history. A place that would be able to make them available to researchers and students. Ideally a place with a proven track record, one that, perhaps, might be able to exhibit items from the collection from time to time. But no such place existed.

So I tried to learn more about Chinese museums that housed collections on Chinese calligraphy and book history, thinking they might be interested in extending their “communications-based” collections forward in time. There was a problem, however: museums that collect Chinese works of calligraphy or woodblock prints tend to think of them as art, not technology. When I shared pictures of typewriters, telegraph code books, Chinese encoding systems, the response was uniform: we focus on art. This isn’t art. Try a science and technology museum.

So the collection stayed where it was: in my office, my small library carrel, my home, my garage. No access for students or researchers. No archival-quality conservation. No exhibitions. Any number of misfortunes – fire, earthquake, broken plumbing, me being hit by a bus – could have led to destruction or dispersal.

And the scale of loss in this field was already enormous: the first Chinese typewriter ever built, by Devello Sheffield in Tongzhou? Gone. The next two experimental prototypes for Chinese typewriters, built by Qi Xuan and Zhou Houkun in the 1910s? Gone. The first electric Chinese typewriter, prototyped by IBM? One survives in a private collection in Delaware, and another just surfaced in a European auction, sold to lord knows who.

Even mass-produced Chinese machines went the same route. Just three of the Commercial Press machines – the first mass-manufactured Chinese typewriters – can be found anywhere in the world: one in Shanghai, in a private collection; one in California, in the Huntington Library; and one in New York, at the Museum of Chinese in America – a museum that only recently confronted a massive conflagration that damaged or destroyed a large portion of its holdings (mercifully, the typewriter was spared).

Maybe more will pop up at some point, but the scale at which Chinese IT history has been lost is nothing short of tragic.

After a long string of rejections and fruitless queries to American and European museums, I began to see a pattern, formed over the course of nearly 150 years, in which China’s achievements in information technology have been systematically disregarded across the board. Rather than seeing Chinese telegraphy, typewriting and computing for what they really were – a series of fascinating and profoundly important puzzles, involving linguistics and precision engineering in equal measures – all the Western world could see was a joke.

Imagine yourself at the dawn of telegraphy, in the 1840s, trying to invent Morse code for Chinese. Later, how do you send Chinese by wire, when Chinese has no alphabet? How do you fit thousands of characters onto a machine with fewer than 50 keys? Or perhaps you are in the 1950s, trying to invent the first Chinese computer. How do you fit Chinese onto a qwerty keyboard?

If still unconvinced, I would now lead the angry TikToker back to the summer of 2009, as I scoured the antiques markets of Beijing trying to locate models of Chinese typewriter that had escaped my analysis. One by one, I inquired with each and every stall at the world-renowned Panjiayuan market, whose selection of wares seemed to indicate a broader interest in gadgets (those selling clocks and cameras were special targets). Each salesperson took my initial question to mean qwerty typewriters, and I began to add emphasis. “I am looking for Chinese typewriters,” I asked (in Chinese), mimicking the act of typing on the tray bed-style machine. Most responded in the negative while others sent me to other aisles which yielded nothing.

Although I did not expect to find one, the reaction of one man was particularly striking. In his mid to late 60s – an age bracket that would have put him in the heart of Chinese typewriter usage – his response was clearest of all: “meiyou”. He did not mean meiyou in the local sense of the word – as in “I do not have one”. Rather, he was using meiyou in the global, existential sense of the word: that such a thing does not exist. That there is no such thing as a Chinese typewriter.

Nothing accelerates time like news of a new baby. With our second child on the way, and my collection swallowing up ever-larger swathes of my home and office, the alarm finally sounded.

I decided to look at my immediate surroundings, my home institution. Stanford houses some of the most important collections on Western computing, not to mention the new Silicon Valley Archives that is set to open later this year, so I checked in with the head of the library and laid out the details. Within 30 minutes I received an enthusiastic and detailed response. They would love to take the collection and give it a home. They would keep the machines and the paper together. They would ensure longevity and accessibility, to any and all individuals regardless of their affiliation. And we could start the process right away.

When the digital ink dried on the agreement, and the fine-arts movers packed up the collection, it was one of the proudest moments of my career – and both my wife and I were thrilled at all the new baby space.

So there you have it. My angry TikToker has at least the opportunity to understand: there is no person, or country, to which I could have “returned” this collection. So I did the next best thing: kept it close but for everyone to see. And with this profession of intent I hope the emojis floated my way in future will include fewer of the angry sort.

But on the internet, about China, perhaps there is not much chance of that.

Source: scmp.com