©2021 Reporters Post24. All Rights Reserved.

A celebration of the island nation’s Sri Lankan food with dishes from Rambutan, the new cookbook by economist turned restaurateur Cynthia Shanmugalingam ,growing up in Coventry in the 1980s and 90s, Cynthia Shanmugalingam recalls being faintly embarrassed by Sri Lankan food. She has a vivid memory of her friend Amy coming over to her house when they were 15. As usual, Shanmugalingam’s mum set up Amy and Cynthia in one room, eating fish and chips, while in another room the rest of the family had a selection of curries and rice.

“I don’t know why we did that,” Shanmugalingam says. “It’s not like somebody said our food was disgusting or anything, but maybe it was an inherited perception. Anyway, Amy said, ‘Can I have what you’re having in there?’ And I was like, ‘Don’t ruin the chips! It’s the only time I’m allowed to eat them.’ I remember my parents saying to Amy, ‘I don’t think you’ll like it.’ But she said, ‘Can I just try it?’ She thought it was delicious. That was a turning point for me.”

Now in her early 40s, Shanmugalingam considers Sri Lankan food to be “one of the world’s most unsung cuisines”. She is hoping to help change that, first with a very personal cookbook, Rambutan: Sri Lankan food, and then in the autumn by opening a restaurant of the same name in London’s Borough Market. Shanmugalingam wasn’t planning for the two ventures to run so close together, but her “pandemic baby” turned into pandemic twins.

What defines and distinguishes Sri Lankan food? Well, curries definitely are at the heart of it. “If it moves, we can curry it,” Shanmugalingam likes to joke. But what makes it unique, she thinks, are the different cultures and colonisers that have tweaked the cuisine over the centuries: Javanese, Malay, Indian, Arab, Portuguese, Dutch and British among them. Coconut milk and oil are more abundant than butter or ghee; there’s phenomenal seafood from shallow lagoon waters; dal and rotis from southern India. “It’s a melting pot of all these different influences,” Shanmugalingam says.

There are a few reasons, she believes, that Sri Lankan food isn’t better known outside its borders. The obvious one is the 25-year civil war that started in 1983 between the Sinhala majority government and Tamil rebels. The country remains profoundly turbulent: shortages of food, fuel and medicines have left it on the brink of collapse this year. “For a country so beautiful and interesting,” Shanmugalingam says, “it’s not as travelled to as it could have been if it hadn’t elected a series of idiots.”

Shanmugalingam, whose parents left for the UK in the 1960s, also suggests another factor. “Sri Lankan tend to do sensible jobs,” she says. “My sister’s a doctor and my cousins are actuaries. I studied economics, which I always say is like doing fine art if you’re Sri Lankan. It’s the most out-there thing you’re allowed to do.”

The result is a cookbook that somehow feels fresh but familiar. Partly because of the bounty of coconut oil, fruit and vegetables in Sri Lanka, more than half the recipes in Rambutan are vegan. “I’m technically Hindu,” Shanmugalingam says, “and most of us don’t eat meat on Fridays. Most of us are part-time vegetarian basically.”

Shanmugalingam is hopeful that Rambutan represents the best of Sri Lankan at a difficult time for the country. “People borrow and exchange a lot,” she says. “Then there are dishes that everybody knows are the best: like crab curry from Jaffna or black pork belly curry from the south. So, on some things, we agree.”

Recipes from Rambutan by Cynthia Shanmugalingam

Prawn curry with tamarind (above)

To make it easier, my recipe is made either with raw shelled prawns, or prawns you have shelled yourself. If you have time and want the flavour bomb of the original, it’s worth the effort to get shelling, and then to spend two minutes making a little spicy prawn oil with the shells and heads. It sounds like it could be a bit cheffy or oily, but it’s super-easy and makes for a glossy, complex, glorious dish. Instructions for both methods are below.

Serves 2

raw prawns 500g with shells on (300g without)

coconut or vegetable oil 1 tbsp, plus 2 tbsp for the prawn oil

Sri Lankan (SL) curry powder 2 tsp (see below), plus 1 tsp for the prawn oil

tamarind block 1½ golf-ball-sized pieces, soaked in 60ml warm water for 10 minutes

red onion 1, peeled and finely sliced

fresh curry leaves 10

garlic 1 clove, peeled and finely sliced

fresh ginger 2cm piece, peeled and finely sliced

salt a pinch

coconut milk 200ml

lime ½

For Sri Lankan (SL) curry powder

coriander seeds 30g

cumin seeds 15g

fennel seeds 15g

black peppercorns 15g

coconut or vegetable oil 2 tbsp

fresh curry leaves 8-10

dried Kashmiri or medium hot red chillies 70g

ground turmeric ¼ tsp

It’s worth making your own batch of SL curry powder. It takes 10 minutes and will keep in the fridge in a jar for three months, but feel free to scale the quantities up or down depending on your needs.

Make sure the windows are open and the ventilation is on, because roasting the chillies will kick up an intense smell that carries through the house. In a dry pan over a low-medium heat, roast the coriander, cumin and fennel seeds and black peppercorns for 1-2 minutes, stirring regularly, until they begin to be really fragrant, then pour them into a bowl. Add the oil to the pan, and cook the curry leaves and dried chillies for 2-3 minutes, stirring often. Remove from the heat and when cool, blitz in a spice grinder or mini food processor until fine – you can blitz it in batches if you need to. Stir in the turmeric, and put the whole lot in a jam jar

If you’re making the prawn oil, place a sieve over a heatproof bowl. Heat 2 tablespoons of oil in a wok or medium-sized pan over a high heat. When it’s shimmering and hot, add the prawn heads and shells and 1 teaspoon of SL curry powder. Stir-fry vigorously for 7-8 minutes, until the shells are pink; give the heads a bit of a squeeze with the end of your spoon as you go, as they’re full of sweet flavour. Switch off the heat, and pass the prawn oil through your sieve into the bowl, discarding any prawn shells left in the sieve.

To make the Sri Lankan curry, squeeze the tamarind with your fingers, then discard the seeds and skin, leaving behind the pulpy water. Add 1 tablespoon of oil to your wok or pan over a medium-high heat. Fry the onion for 4-5 minutes, stirring occasionally, until soft. Add the curry leaves, garlic and ginger. Stir-fry for 30 seconds until the garlic is just getting fragrant, then stir in the tamarind water, 2 teaspoons of SL curry powder and the salt, and bring to a boil.

Turn the heat down to a simmer and cook through for 2-3 minutes. Finally, add the prawns and coconut milk, and stir through. Bring back to a simmer and cook for 3-4 minutes – no more or the prawns will overcook.

Switch off the heat and if you have it, pour the prawn oil into the curry and stir it in gently so that it is nice and glossy. Dish up, and finish with a generous squeeze of lime.

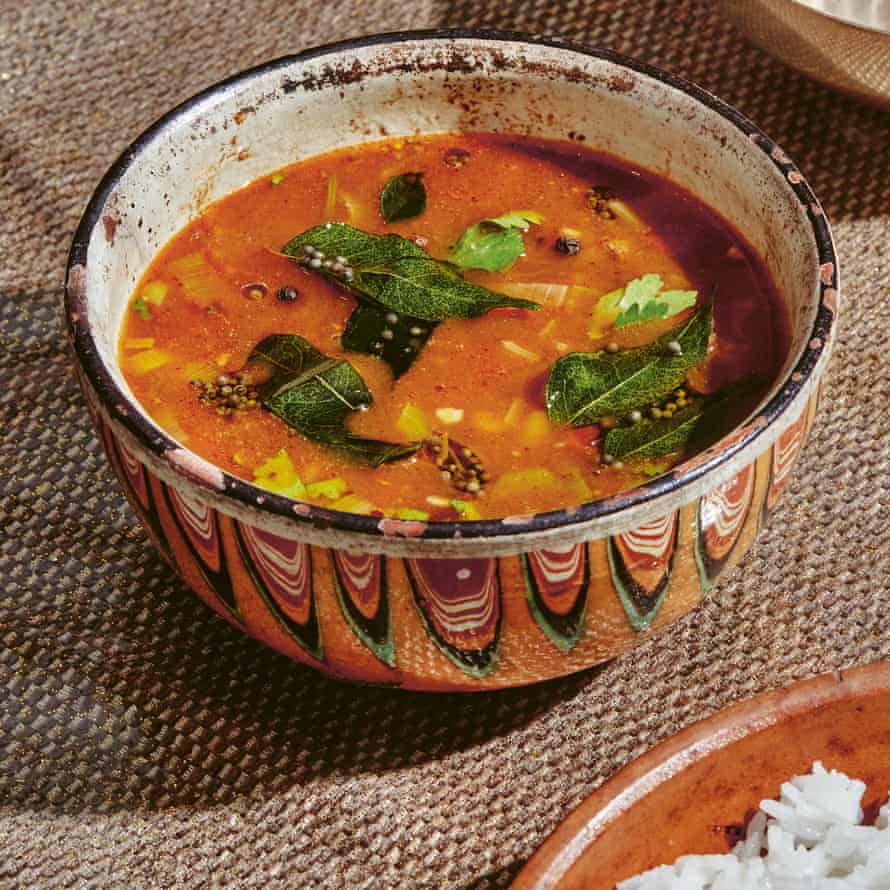

Tomato rasam broth with leek and coriander

An ancient dish with south Indian Tamil roots, Sri Lankan rasam is a hot, clearing broth of tamarind, black pepper and cumin, with different variations depending on your feelings. “Rasa” in Tamil means the essence, the mood, the taste, the jam, the thing that makes you feel something and it gets to something deep inside. I like to have it with a dollop of yoghurt and plain rice on cold days, and I like to add leeks because it’s a way to eat more vegetables and their sweet greenness is so good in the tangy broth.

Serves 2

tamarind block 3 golf-ball-sized pieces, soaked in 240ml warm water for 10 minutes (see note at end of recipe)

coconut or vegetable oil 2 tbsp

tomatoes 2 medium (about 200g), roughly chopped

salt 1 tsp, or to taste

leek 1, light green parts halved and sliced into ½cm-thick slices

fresh coriander leaves ½ small handful, roughly chopped

For the rasam spice mix

cumin seeds 3 tsp

black peppercorns 2 tsp

dried red chillies 3

garlic 5 cloves, peeled and halved

For the temper

coconut or vegetable oil 2 tbsp

fresh curry leaves 10

mustard seeds 1 tsp

First, make your rasam spice mix. Set a small frying pan over a medium heat and add the cumin seeds, black peppercorns, chillies and garlic. Heat, stirring occasionally for 1-2 minutes until fragrant, being careful not to burn the spices. Once cool, put all the ingredients in a spice grinder, mini food processor or pestle and mortar, and blitz to a coarse paste, adding a little water if necessary.

To make the rasam broth, squeeze the soaked tamarind with your fingers, then discard the seeds and skin, leaving behind the pulpy water. Heat the oil in a small saucepan, and when hot add the tomatoes. Saute for about 4 minutes, until they begin to soften. Then add the tamarind water, rasam spice mix, salt and leek. Simmer gently over a low heat for 4-5 minutes; it should be very fragrant. Remove from the heat and pour into serving bowls. Add a couple of tablespoons of cold water, and stir in the coriander leaves.

To make the temper, heat the oil in a small frying pan set over a medium heat. When hot, add the curry leaves, which should crisp up, and mustard seeds, and cook until they splutter. Pour the whole lot, oil and all, on to your rasam and serve.

Green beans white curry

I love tender, sweet green beans and this mild, aromatic coconut milk curry is a great weeknight way to cook them. The temper is with fenugreek, which makes for a kind of caramel-like finish.

Serves 2

coconut or vegetable oil 1 tbsp

red onion 1, peeled and finely sliced

coriander seeds ¾ tsp

cumin seeds ½ tsp

fennel seeds ¼ tsp

fresh curry leaves 5

water 125ml

green beans 250g, sliced diagonally into 3cm-long pieces

ground turmeric 1 tsp

green chillies 2, sliced

coconut milk 100ml

lime ½

coconut or vegetable oil 1 tsp

fresh curry leaves 10

fenugreek seeds 1 tsp

black pepper a generous couple of grinds

Heat the oil in a pan over a medium-high heat and fry the onion for 5-6 minutes, until translucent. Add the coriander, cumin and fennel seeds and curry leaves, then cook for 4-5 minutes until the leaves are bright green.

Add the water and sliced green beans, along with the turmeric and green chillies. Cook for 5-7 minutes, until the beans are bright green.

Stir in the coconut milk and add a little salt. Bring to a gentle boil, then turn down and simmer for 3-4 minutes, until the beans are tender and just cooked through. Switch off the heat.

In a small frying pan, make the temper. Heat the oil over a medium-high heat, and when sizzling add the curry leaves, fenugreek seeds and black pepper. After about 30 seconds or 1 minute, when the curry leaves are crispy, pour the whole lot on to the curry and stir through. Finish with a squeeze of lime.

Red fish curry

This curry wants a meaty, fleshy fish with plenty of flavour. The onions on top aren’t traditional but I think they make it crunchy and tasty. Try it with a bean curry or a greens curry.

Serves 4

tamarind block 1 golf-ball-sized piece, soaked in 125ml warm water for 10 minutes

coconut or vegetable oil 1 tbsp

red onion ½, peeled and finely sliced

fresh curry leaves 7

garlic 2 cloves, peeled and halved

fresh ginger 4cm, peeled and sliced

tomatoes 2 medium (about 200g), roughly chopped

ground turmeric ½ tsp

SL curry powder 2 tbsp (see prawn curry recipe)

salt 1 tsp, or to taste

hake or firm white fish fillet 450g, cut in half lengthways then into 6cm chunks

water 250ml

coconut milk 100ml

lime 1

For the temper

coconut or vegetable oil 1 tbsp

red onion ½, peeled and finely sliced

fresh curry leaves 8

Squeeze the tamarind with your fingers, then discard the seeds and skin, leaving behind the pulpy water. In a medium-sized saucepan or wok, heat the oil over a medium heat and fry the onion for 8-10 minutes until soft. Add the curry leaves and after 30 seconds, when they are bright green, stir in the garlic and ginger.

After about 30 seconds, when the garlic is beginning to turn golden, add the tomatoes and tamarind water and cook for 3-4 minutes, stirring occasionally.

When the tomatoes have cooked down a little, add the turmeric, SL curry powder and the salt. Slide the fish into the pan, and pour in the water. Allow to come to a gentle boil, then turn the heat down to a simmer, cover the pan with a lid and cook for 10 minutes.

Stir in the coconut milk and allow to come back to a simmer, then cook for a further 10 minutes or so, until the fish is cooked through. You can test it by gently flaking a piece with a fork: it should be opaque all the way through, and flake easily.

Serve the fish with the temper, and all its oil, spooned over the top. Squeeze over the lime.

Coconut milk greens curry

There are more than 110 native varieties of spinach-like greens in Sri Lanka. There are hundreds of recipes, but this is the most common and my favourite. It is a wet, fragrant mix of spinach – or any greens, such as chard, kale, spring greens – cooked in thick coconut milk, turmeric, black pepper and cumin. It’s very simple and healthy.

Serves 4

coconut or vegetable oil 2 tbsp

red onion 1, peeled and finely sliced

garlic 3 cloves, peeled and sliced

ground turmeric 1 tsp

cumin seeds 1 tsp

salt and black pepper

green chillies 3, sliced

baby spinach or kale 4 handfuls, washed (about 400g)

water 200ml

coconut milk 200ml

lime ½

Heat the oil in a wok or frying pan over a medium heat. Add the onion and garlic, stirring occasionally until the onion is translucent and starting to brown at the edges. Sprinkle in the turmeric, cumin, about a teaspoon of salt, and the green chillies. Give it a good mix, then cook for about 1 minute until the spices are fragrant.

Add the spinach, the water and the coconut milk, and cook with the lid on over a high flame for 3-7 minutes, depending on what greens you are using (baby spinach cooks faster than kale). You want them to be bright green but soft when you bite into it.

Remove from the heat, taste the curry and adjust with salt if needed. Plate up and finish with a generous squeeze of lime and a couple of generous grinds of black pepper.

Flaky paratha

These flaky, crisp parathas are kind of like the all-butter croissants of rotis. Made from delicious layers of dough, they are great fun to try. You first drip the dough with oil, roll it out so it gets nice and thin, coil it up into snail-shaped spirals and then roll it. They’re not usually made at home, this is more of a cafe or takeaway treat.

Makes 4-6

plain white flour 240g

salt ½ tsp, or to taste

granulated sugar ½ tsp

vegetable oil 80ml, plus more for oiling and frying

water 70ml

Put the flour, salt, sugar, 80ml of vegetable oil and the water in a mixing bowl. Using your hands, bring it together to form a dough, then knead it thoroughly for 5 minutes in the bowl or on an oiled surface. It should feel smooth and a little sticky, but it shouldn’t be stiff or crumbly – if it is too crumbly, add a tablespoon of oil and a tablespoon of water, and work that in.

Leave the dough in the bowl covered with a damp clean tea towel to rest at room temperature for 2 hours.

Divide and shape the dough into 4–6 balls and rest the dough balls for a further 5 minutes under the damp tea towel.

To roll them out, drip a little oil on to a rolling pin and lightly oil your work surface. Roll out each dough ball into a little disc, 12–15cm in diameter. Sprinkle with a little more oil.

Use your fingers to lift and gently stretch out the dough until it is 1mm or so thin. When it’s very thin (don’t worry if you get a few holes), pinch together a corner between one thumb and index finger, and an opposite corner in your other hand, and pull the two ends into a single line, so you get a kind of pleated effect. Then curl the line of dough round to make a snail or pain au raisin shape. Repeat with all the dough discs. Rest the snails for 5 minutes on a baking tray, covered in a damp clean tea towel.

When you’re ready to cook, roll out the dough snails with a rolling pin to make roughly 15cm circles. Oil up a frying pan with a little drizzle of oil, and place over a high heat. When hot, cook each paratha for about 1 minute on each side until nice and golden. Then turn the heat right down and cook for 1 minute on each side on a low heat.

Puff up the paratha a little by gently clapping its sides, then serve.

The Observer aims to publish recipes for sustainable fish. Check ratings in your region: UK; Australia; US

Rambutan by Cynthia Shanmugalingam (Bloomsbury, £26). To support The Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

… we have a small favour to ask. Millions are turning to the Guardian for open, independent, quality news every day, and readers in 180 countries around the world now support us financially.

We believe everyone deserves access to information that’s grounded in science and truth, and analysis rooted in authority and integrity. That’s why we made a different choice: to keep our reporting open for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. This means more people can be better informed, united, and inspired to take meaningful action.

In these perilous times, a truth-seeking global news organisation like the Guardian is essential. We have no shareholders or billionaire owner, meaning our journalism is free from commercial and political influence – this makes us different. When it’s never been more important, our independence allows us to fearlessly investigate, challenge and expose those in power.