©2021 Reporters Post24. All Rights Reserved.

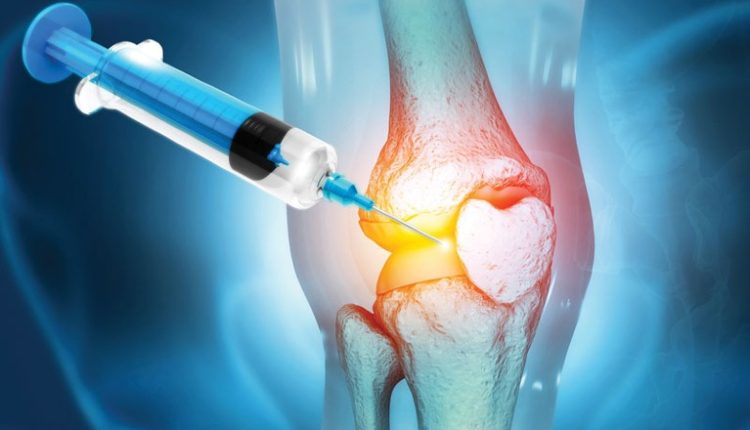

A simple injection that blocks an age-linked protein regrows knee cartilage in older mice and prevents arthritis after knee damage. Human knee tissue exposed to the same blocker starts forming new cartilage, opening a path beyond pain medicine and joint replacement.

Red-stained slices of mouse knees showed the cartilage layer thickened after treatment, even when the animals were already old.

By tracking how much cushion returned, Nidhi Bhutani, Ph.D., at Stanford Medicine tied the regrowth to blocking one protein.

Her team tested both belly and joint injections and saw cartilage rebuild across the knee surface, not just in one spot.

Such regrowth clashes with a hard truth about knees: once cartilage thins, the body usually cannot replace it on demand.

Why knees fail

Across the United States, arthritis affects about one in five adults and keeps orthopedic waiting rooms busy.

In knee osteoarthritis, a slow joint disease that wears down cartilage, cartilage cells send inflammatory signals and the joint loses its smooth glide.

Without a fresh cartilage layer, bones rub more, swelling follows, and everyday moves like standing or stairs can feel like a grind.

Comments are closed.